Experiments with AI Coding

AI coding has become substantially better in the last six months. As I am soon starting a job to build RL environments to improve coding agents, I wish to get a better understanding of abilities and limitations of the current technology.

In this blog post, I evaluate how useful these tools are at solving my problems by trying to unblock various stale side projects. This is not with respect to any benchmark other than my personal real life usage.

All observations are as of early January 2026.

Overall Takeaways

If you don’t want to read a long post, here are my quick takeaways:

- An experienced developer is still needed to use these tools most effectively, pointing them in the correct direction and evaluating their decisions within a problem domain.

- I found agent speed and difficulty expressing the full nature of the problem to be my limiting factor in use. Given enough time, I could often force the agent to solve most easy-medium difficulty problems, especially when a verification loop is accessible to the agent. On harder problems, I usually gave up and did it myself.

- Acceptance criteria varies by problem domain, and AI output code is often bloated. In some use cases like frontend, this is less of an issue, in others like performance-intensive code, each line matters.

- Intelligence in models matters. The difference between Opus 4.5 and other alternatives is significant, and can minimize overall iterations needed as well as enable more complex tasks. Agentic IDEs have become good enough that the ball is back in the court of model development.

Tools Used

I primarily use neovim+tmux as my editor setup, preferring to be closer to the terminal. Many popular tools (Cursor, Antigravity, Windsurf, etc.) are based on VSCode-style workflows, which often feel inelegant to me. This does not stop me from using these tools, but I find them less useful because I feel an inherent slowdown that contrasts whatever AI benefits I get.

As such, I am actively looking for terminal-native AI coding tools and ways to integrate into my existing neovim workflows.

SuperMaven (Autocomplete)

Supermaven is the autocomplete engine used (and acquired) by Cursor. However, you can still use it in other editors, with a generous free tier. It is the only AI-autocomplete I have tried that is as fast as an LSP, and what I use in neovim.

OpenCode (Agentic)

OpenCode is a CLI tool similar to Claude Code, but designed for support of any models on OpenRouter, and created by neovim users. Like many such tools, it consists of distinct “Plan” and “Build” agents, where you discuss with an agent that looks at the code base, and only once you are satisfied with the plan, you enable the agent to edit code and build it. I found this workflow to be an improvement over other methods, allowing agents to take full advantage of reasoning abilities. The hotkeys and ui were also relatively nice as a TUI application. I mostly used OpenCode outside of neovim in a separate tmux tab, and then ran and read the code afterwards to validate the results.

I found OpenCode to be relatively good at providing models the tools to access the internet and my codebase, with reasonable permissions. Most of the problems described n this post seem to be limitations of the models themselves, and as such, I did not try any other agentic tools within this testing.

Models

Anthropic’s Opus 4.5 is considered the gold standard in agentic coding, while being significantly more expensive. I attempted to use cheaper alternatives when possible, but when they could not solve the problem, I used Opus 4.5.

OpenCode has their own fine-tuned model (similar to Cursor’s Composer) that was available for free. I used this in initial testing and it performed reasonably well for simple tasks.

GLM 4.7 was newly released during this project, and I switched to it over OpenCode’s model. This model seemed to be good at understanding what was happening in the codebase, and is quite good at frontend while being much cheaper than Anthropic models.

Tasks Attempted

Personal Site

After putting this off for awhile, I finally updated my personal site with cleaner styling to host blog posts and showcase projects. I built it as a static site with Astro, using shadcn as a reference. GLM 4.7 and OpenCode’s model proved more than sufficient for this task, quickly generating boilerplate that would have taken hours manually. Theming and other high-level edits worked smoothly through natural language, while complex animations required more back-and-forth to fix broken behavior.

These models spent similar time on edits regardless of size, often taking considerable time to read through HTML and find optimal modification points. For smaller changes, manual edits were much faster. Astro’s minimal framework made validating and editing LLM-generated HTML/CSS relatively straightfoward. Since the codebase worked in separate files, I could queue up multiple agents in parallel for different tasks and bounce between them for feedback.

I don’t particularly enjoy writing frontend code, so I focused on writing blog posts while agents handled the styling in the background.

You’re looking at the result: iamr.site. It’s not perfect, but it works for my needs.

ML Deployment to WebAssembly

Seeing success in web development, I decided to try a harder task with more boilerplate.

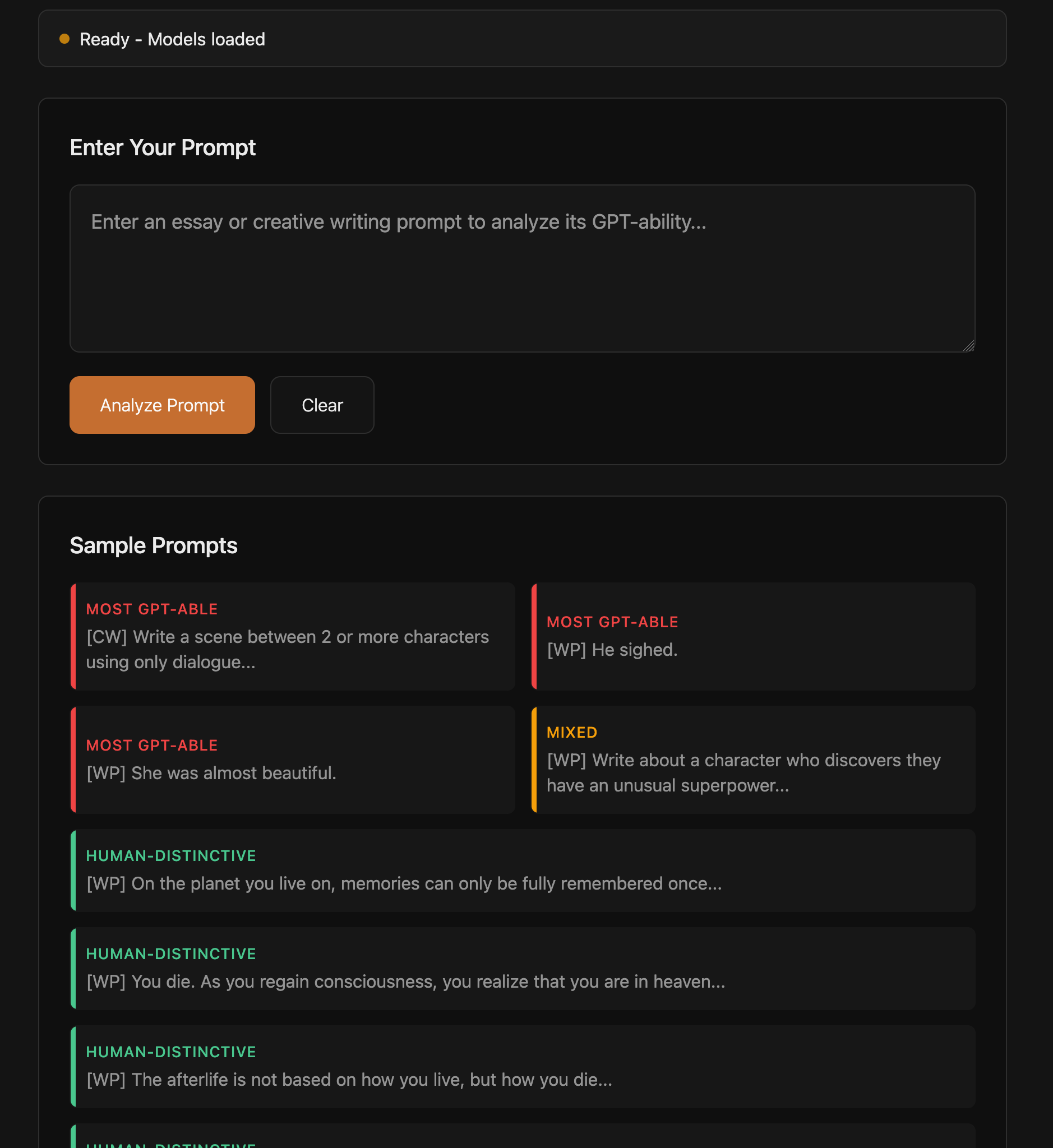

For some other research, I trained a small transformer model in PyTorch to classify assignments as more or less “GPT-able”, to try to help educators better test students. I wanted to deploy this in a way that it could run locally in the browser via WebAssembly. WebAssembly toolchains are often a pain to work with, combining code in multiple languages that has to be shipped to the browser in a very particular way. This task is still not intellectually complex, but requires a lot of googling and fiddling with the environment to get everything to build properly. The final approach involved compiling the model to ONNX format and quantizing it, and then loading that model into an ONNX web runtime and Transformers.js.

These interconnected pieces proved too much for the weaker models to handle. OpenCode’s model generated large amounts of files that produced a pretty frontend in the browser, but failed to load the actual model and produce outputs.

The intelligence boost of Opus 4.5 was able to complete the problem, and its solution was much simpler than the previous AI attempts. It identified subtleties the other models did not notice, such as that the model used a pretrained embedding, which could be loaded from a separate optimized source for more efficiency. Because I had a paper written on the project, the agent was able to efficiently understand the context of what this model was doing, and able to pull examples and language from the paper, producing a quality interactive tool. Like the weaker models, Opus’ page did not work on first attempt. However, after pasting console error messages back to the agent a couple times, it was able to solve the problem where weaker models got stuck in a loop.

This process was not cheap. Even in an environment with minimal files and well-formed context, this generation cost ~$8 of inference. Given my unfamiliarity, this probably would have taken me a couple hours of work, so a reasonable amount of time was saved. I suspect someone familiar with the space could get it done in under half an hour.

The code produced in this process was well documented by the agent; the commit can be viewed here. The results of this effort can be viewed at iamr.site/gptability.

Bespoke QR Code Generator

I now decided to test the ability to transfer code over from another code base, as well as work in a less common language. I previously wrote a QR code generator from scratch in the programming language nim, which compiles to both assembly (through LLVM) and javascript for web deployments.

The first task for the coding agent was to take the existing webpage and integrate it into my current site, standardizing the styling and linking some navigation. This task wasn’t particularly difficult; the result is deployed at iamr.site/qr.

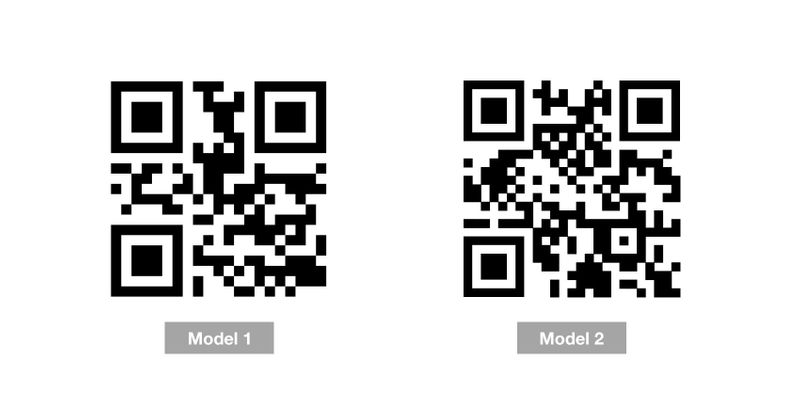

The much harder task I gave Opus 4.5 was to extend the existing nim code. I implemented the most basic version of the QR code specification, which only supports URLs of 17 characters. The higher versions of the specification are more complicated, combining extensions to the error correcting algorithm as well as spatial reasoning about different formats. This task was admittedly quite difficult, but I was curious if such knowledge was within its training data or if it could look up existing implementations and translate them to another language.

Opus 4.5 produced nim code that compiled correctly and output a QR code of the correct size that looked reminiscent of the extended specification. However, these QR codes do not pass the test of an external reader. After prompting the model that its code did not work, it introspected further, but without a checker integrated into the loop, it was unable to make progress on the problem. This process cost $13.29 to generate no useful results, and I cut it off at this point. For those curious about the attempt, the changes can be found here.

Game Development

With some knowledge of easy and hard tasks for coding agents, I wished to experiment with more medium difficulty tasks to find the exact lines of competence. Game development is a space with a lot of code to be written, with a rich environment of varying levels of complexity and boilerplate.

I revisited a project where I was writing a small pathing engine for an RTS game using zig and raylib. For my purposes, this problem boils down to creating responsive multi-agent pathing and control in a 2 or 2.5 dimensional environment. I’ll write up a future blog post about the goals and challenges of this project, but think of this as within the algorithms and performance domain.

This project was in early stages when I started, consisting of just a rendered grid and mouse selection. GLM 4.7 was able to bring this up to interactive single agent pathing in an environment with obstacles. This was within the realm of common tasks, but still impressive that it output an A* implementation in zig.

After the point, the project grew more complex as I implemented multiagent pathing while minimizing collisions. This required modifying existing algorithms and creating a unique planner. After upgrading to Opus 4.5 again, I encountered a new challenge explaining the problem and my priorities. While Opus generated a solution that addressed the problem, it added unnecessary complexity and solved additional issues I didn’t request.

For this example I’ll go through the exact code, particularly the diffs between Opus’s implementation and my own implementation afterwards.

The specifics of this task were to 1) allow the selection of multiple agents and then 2) pick a set of goals for them based around the clicked point. Because the paths needed to not collide, more than one location needed to be picked around the goal. At this point, the task was only to pick the goals, not to force the pathing algorithm to avoid overlapping individual agent paths. I went back and forth with the agent for some time in planning to explain this situation, as well as emphasize simplicity as a virtue when picking between multiple approaches. To me, the easiest solution to this problem would be a simple BFS around the target point, and then assigning agents arbitrarily to the points.

// my solution

pub fn getGroupGoals(obstacles: *ObstacleGrid, goal: ScreenPos, ...) !std.ArrayList(ScreenPos) {

var goals = std.ArrayList(ScreenPos).empty;

var taken = std.AutoHashMap(ScreenPos, void).init(allocator);

var toVisit = queue.Queue(ScreenPos).init(allocator);

defer toVisit.deinit();

try toVisit.enqueue(goal);

try taken.put(goal, {});

// bfs

while (goals.items.len < count) {

const curr = toVisit.dequeue().?;

if (obstacles.obstacles.get(map.screenToGridCoord(curr, gridSize))) |height| {

if (height >= 3) {

continue;

}

}

try goals.append(allocator, curr);

for (crossDiagonalMovement) |move| {

const movedPoint: ScreenPos = .{ .x = curr.x + move[0] * gridSize, .y = curr.y + move[1] * gridSize };

if (taken.get(movedPoint)) |_| {} else {

try taken.put(movedPoint, {});

try toVisit.enqueue(movedPoint);

}

}

}

return goals;

}Opus 4.5 implemented a much more complex algorithm, using a modified BFS with a range, calculating a centroid of the agents, and then placing them within a target region based on their offset from the centroid. This algorithm does solve other problems not asked, however it is also 4-5x longer than my intended solution, and introduces far more edge cases and interactions. I’ve added an (abridged) version of the code below just to convey how much additional complexity this adds. There are also small bugs that went unannotated in the code, such as claiming the traversal was a BFS while using a data structure that would yield a DFS.

// agent solution (some parts omitted)

fn gatherAvailableCells(

targetPos: ScreenPos,

count: usize,

gridSize: i32,

obstacleGrid: *const ObstacleGrid,

maxSearchRadius: i32,

allocator: std.mem.Allocator,

) !std.ArrayList(ScreenPos) {

var result = std.ArrayList(ScreenPos).empty;

errdefer result.deinit(allocator);

// NOT ACTUALLY A QUEUE, yields a DFS

var queue = std.ArrayList(ScreenPos).empty;

defer queue.deinit(allocator);

// <same bfs logic>

}

pub fn findGroupGoals(

targetPos: ScreenPos,

agents: []const Agent,

gridSize: i32,

obstacleGrid: *const ObstacleGrid,

allocator: std.mem.Allocator,

maxSearchRadius: i32,

) !std.ArrayList(ScreenPos) {

var result = std.ArrayList(ScreenPos).empty;

errdefer result.deinit(allocator);

// Count selected agents and calculate centroid

var selectedCount: usize = 0;

var centroidX: i64 = 0;

var centroidY: i64 = 0;

for (agents) |agent| {

if (agent.selected) {

selectedCount += 1;

centroidX += agent.pos.x;

centroidY += agent.pos.y;

}

}

if (selectedCount == 0) {

return result;

}

centroidX = @divFloor(centroidX, @as(i64, @intCast(selectedCount)));

centroidY = @divFloor(centroidY, @as(i64, @intCast(selectedCount)));

// Snap target to grid center

const targetSquare = grid.getSquareInGrid(gridSize, targetPos);

const targetCenter = grid.getSquareCenter(gridSize, targetSquare);

// Gather available cells near target (more than needed for flexibility)

var availableCells = try gatherAvailableCells(

targetCenter,

selectedCount * 4,

gridSize,

obstacleGrid,

maxSearchRadius,

allocator,

);

defer availableCells.deinit(allocator);

// Track which cells have been assigned

var assignedCells = std.AutoHashMap(ScreenPos, void).init(allocator);

defer assignedCells.deinit();

// For each selected agent, find the best matching cell

for (agents) |agent| {

if (!agent.selected) continue;

// Compute agent's direction from centroid

const agentDx = agent.pos.x - @as(i32, @intCast(centroidX));

const agentDy = agent.pos.y - @as(i32, @intCast(centroidY));

// Check if agent is at centroid (or very close)

const atCentroid = (@abs(agentDx) < gridSize and @abs(agentDy) < gridSize);

const agentAngle = computeAngle(agentDx, agentDy);

// Find best matching cell

var bestCell: ?ScreenPos = null;

var bestScore: f32 = std.math.inf(f32);

for (availableCells.items) |cell| {

if (assignedCells.contains(cell)) continue;

// Compute cell's direction from target

const cellDx = cell.x - targetCenter.x;

const cellDy = cell.y - targetCenter.y;

const cellAtTarget = (cellDx == 0 and cellDy == 0);

// Score = angular difference + small distance penalty for tie-breaking

var score: f32 = 0;

if (atCentroid) {

// Agent at centroid prefers cells closest to target

const dist = @as(f32, @floatFromInt(@abs(cellDx) + @abs(cellDy)));

score = dist;

} else if (cellAtTarget) {

// Target cell has no angle - give it a moderate score

// (center-most agents will claim it due to their low scores)

score = std.math.pi;

} else {

const cellAngle = computeAngle(cellDx, cellDy);

const angularDiff = angleDifference(agentAngle, cellAngle);

// Distance from target as tie-breaker (normalized)

const dist = @as(f32, @floatFromInt(@abs(cellDx) + @abs(cellDy)));

const distPenalty = dist / @as(f32, @intCast(gridSize * 100));

score = angularDiff + distPenalty;

}

if (score < bestScore) {

bestScore = score;

bestCell = cell;

}

}

// Assign cell (or fallback to agent's current position)

if (bestCell) |cell| {

try assignedCells.put(cell, {});

try result.append(allocator, cell);

} else {

// Fallback: use agent's current position

const agentSquare = grid.getSquareInGrid(gridSize, agent.pos);

const agentCenter = grid.getSquareCenter(gridSize, agentSquare);

try result.append(allocator, agentCenter);

}

}

return result;

}This example highlights the particular challenges of using AI code within this domain. The solution does work, and if you didn’t look at the code, you might consider it sufficient. However, this is the simplest piece of what is going to be a multipart pipeline of pathing, and it has added a large amount of complexity and unknown edge cases, while also being foreign for me to read.

The next change needed was to modify the A* algorithm to prevent the paths generated from colliding with each other, now that each agent was going to separate locations. My solution involved a ~30 line modification to compute each agent’s path sequentially, and then keep track of what agent occupied a given location at a given time and mark it impassable in the A* search. This kind of change involved a small amount of code but a lot of thinking on my part on how to structure it. Opus 4.5 attempted a longer change to solve the problem, but was unsuccessful (~$7 lost).

Interestingly, after writing my solution, I used GLM 4.7 to fix a small edge case regarding differing path lengths, and it made that change correctly.

While the agents struggled with pathing problems, they were successful elsewhere in expanding the terrain generation. Originally, the obstacles were placed uniformly randomly in the environment. To have more realistic terrain, I wanted mountain and hill formations of varying heights, easing from high to low. In this effort, I was able to get GLM 4.7 to generate a procedural map generator that used perlin noise to create a graduated height map, and then bezier curves to create mountain ranges. This is one section of code that I almost exclusively use AI generation for, given that the results don’t need to be perfect, and solving the problem myself would be mostly searching up existing solutions.

This project is still under development, but current progress of all these efforts is shown below.

Going forward, I am mostly writing this code by hand, but I will use AI to scaffold out certain kinds of architecture and generate configurations and maps like the terrain.

Compile-time Metaprogramming

As a last unique challenge, I tried building partial application of functions using zig comptime. I didn’t need this feature, but I like it in languages, so I went through the process of adding it to the RTS engine project.

My specific requirements were quite strict. I wanted to be able to pass a function f(a,b,c,d) into partial(.{v_a,v_b}, f) and get a function pointer out that only took c,d as parameters with the other two applied. Zig is a compiled language without garbage collection or first-class functions, so all of this needs to occur at compile time.

Most AI search tools told me this wasn’t possible, and indeed when I forced them to create outputs they weren’t good. I fiddled with comptime programming a little more myself, and wrote a solution. Due to changes in zig 0.15, the construction of this is harder than it used to be, requiring some hard coding of arity with a switch.

// my solution

fn concatTuples(a: anytype, b: anytype) concatType(@TypeOf(a), @TypeOf(b)) {

const T1 = @TypeOf(a);

const T2 = @TypeOf(b);

const len1 = @typeInfo(T1).@"struct".fields.len;

const len2 = @typeInfo(T2).@"struct".fields.len;

var result: concatType(T1, T2) = undefined;

inline for (0..len1) |i| result[i] = a[i];

inline for (0..len2) |i| result[i + len1] = b[i];

return result;

}

fn concatType(comptime T1: type, comptime T2: type) type {

const fields1 = @typeInfo(T1).@"struct".fields;

const fields2 = @typeInfo(T2).@"struct".fields;

var types: [fields1.len + fields2.len]type = undefined;

inline for (fields1, 0..) |f, i| types[i] = f.type;

inline for (fields2, 0..) |f, i| types[i + fields1.len] = f.type;

return std.meta.Tuple(&types);

}

fn makeFunc(comptime T: type, comptime f: anytype, provided: anytype) T {

const info = @typeInfo(T);

const Fn = info.@"fn";

const params = Fn.params;

return switch (params.len) {

0 => struct {

fn wrapper() Fn.return_type.? {

return @call(.auto, f, provided);

}

}.wrapper,

1 => struct {

fn wrapper(a: params[0].type.?) Fn.return_type.? {

const in = concatTuples(provided, .{a});

return @call(.auto, f, in);

}

}.wrapper,

// ...

}

}

fn partialType(comptime args: type, comptime f: type) type {

const args_info = @typeInfo(args);

var f_info = @typeInfo(f);

const original_arg_types = f_info.@"fn".params;

f_info.@"fn".params = original_arg_types[args_info.@"struct".fields.len..];

return @Type(f_info);

}

pub fn partial(args: anytype, comptime f: anytype) partialType(@TypeOf(args), @TypeOf(f)) {

const out_t = partialType(@TypeOf(args), @TypeOf(f));

return makeFunc(out_t, f, args);

}However, I had neglected to test forcing Opus 4.5 initially. When I did, it solved the problem for $1.47 in short order, producing a solution similar to mine but more condensed. I’m still unsure whether that success came from better prompting or an unsanitized environment, but I was surprised by the output quality.

// opus 4.5

fn PartialFn(comptime F: type, comptime n: usize) type {

const info = @typeInfo(F).@"fn";

var new_params: [info.params.len - n]std.builtin.Type.Fn.Param = undefined;

for (info.params[n..], 0..) |p, i| {

new_params[i] = p;

}

return @Type(.{ .@"fn" = .{

.calling_convention = info.calling_convention,

.is_generic = false,

.is_var_args = info.is_var_args,

.return_type = info.return_type,

.params = &new_params,

} });

}

pub fn partial(comptime f: anytype, comptime bound_args: anytype) PartialFn(@TypeOf(f), bound_args.len) {

const F = @TypeOf(f);

const info = @typeInfo(F).@"fn";

const bound_count = bound_args.len;

const remaining_count = info.params.len - bound_count;

const p = info.params;

const Impl = struct {

inline fn callWithArgs(remaining_tuple: std.meta.ArgsTuple(PartialFn(F, bound_count))) info.return_type.? {

var full_args: std.meta.ArgsTuple(F) = undefined;

inline for (0..bound_count) |i| {

full_args[i] = bound_args[i];

}

inline for (0..remaining_count) |i| {

full_args[bound_count + i] = remaining_tuple[i];

}

return @call(.auto, f, full_args);

}

};

return switch (remaining_count) {

0 => struct {

fn call() info.return_type.? {

return Impl.callWithArgs(.{});

}

}.call,

1 => struct {

fn call(a0: p[bound_count].type.?) info.return_type.? {

return Impl.callWithArgs(.{a0});

}

}.call,

//...

}

}This code may seem like a minor deal to most people, but I am impressed that a coding agent could figure out a niche feature in a less popular language and produce working code for an uncommon task. Zig recently pushed breaking changes to this kind of code in their recent release (0.15), and the agent was able to navigate that in context, even though such changes were not in its training data.

Broader Observations

Vibe Waiting and Time Management

I have always favored faster non-reasoning LLMs for searching tasks, such as Gemini Flash, GPT-5.x Instant, Kimi K2 0905, etc. This is because of the classic “code is compiling” problem: if I have to wait long enough, I get distracted from the project and lose productivity from the flow break (checking phone, etc.). These tools take this problem to the extreme, because once you set them running, they may take minutes to give a result. The natural thing to do is start the tool, get distracted and do something unproductive, and only come back when the tool is done. I call this phenomenon “Vibe Waiting,” and I think it should be avoided, even if you are the most bullish AI user.

If you are using AI as part of your workflow, I believe you must not block yourself by waiting on an LLM, otherwise most productivity gains are lost. There are many useful things you can do while an agent runs in the background. You could queue up other agents and hop between managing them, focus on a part of the codebase the AI can’t handle as well, or do research and review other parts of the code. This aspect is why people liken coding agents to managing a team or playing an RTS game: the core idea is to keep yourself unblocked as much as possible and manage your time effectively. The creator of Claude Code recently shared that he will often have six coding agents running in parallel, and then turn on desktop notifications for when each of them need his feedback. I view such time management and multitasking as critically important if you want to take advantage of these agents; otherwise they will actively waste your time and teach you to turn off your brain.

Connection to Code

I view the biggest problem of AI code generation as encouraging reliance on code you don’t read or understand. There are various detrimental effects of not being connected to the codebase that are unique to agent vs traditional coding. One is that if the agent cannot solve your problem, it is often worse to debug code that you didn’t write, and you may be gatekept from your own code by needing to ask the agent for clarification. This is why I believe developers with familiarity in the subject matter, as well as simpler languages and tools, substantially improve the agentic coding experience. The ability for the human to read and edit the code is crucial.

Another issue is understanding the generated code’s actual capabilities. While passing tests help, most software has edge cases and limitations not fully captured in specifications or reported by agents, creating uncertainty about generalizability, special-casing, performance, and future flexibility. As you evaluate agent decisions and direct them toward unsolved problems, your innate understanding of these risks shapes project design. Since agents still rely on human direction, poor technical understanding leads to poor decisions about future changes. This is the same reason we value technical expertise in engineering leadership, not just a business background.

When is AI Good Enough?

I think the efficacy of AI code is deeply tied to acceptance standards in the particular domain. This is partially due to models being trained on some tasks more than others, but also due to how easily a verification loop can be created and how tight the efficiency concerns are. Within these experiments, in frontend I had very low acceptance standards: if the page renders and it looks good enough, I don’t care how it occurred. When I am writing a pathing engine, I very much do care about efficiency and simplicity in the code, so the model is not as helpful. In my QR code case, there was no scaffolding for an incremental verification loop, so the model had to make big jumps without checking its work, and was not able to efficiently make progress. These differences explain why some people think software engineering has been solved by AI while others think it’s absolutely useless. The reality is somewhere in between, and both may be right depending on the problem.

Going Forward

After this exploration, I primarily intend to use coding agents for frontend changes or boilerplate-heavy activities that involve more googling than writing code. For any more complex task, I prefer to write the code and do the setup myself. My current mindset treats AI as a customizable blackbox dependency generator. If I am not willing to import a package I wouldn’t read, I am not willing to use AI code to solve the problem. I make exceptions for changes small enough to read and understand, in languages clear enough that I’m not concerned about hidden behavior.

I have turned off AI autocomplete for most languages. I find that in domains where it is useful, I can allow full-fledged agentic coding, and if it’s not, then it’s usually distracting. I’m not certain I’ll keep it this way; I may turn it on again for more boilerplate-heavy environments.

For me to integrate agentic coding into more workflows, speed is the core improvement needed. Because edits take so long, agents require babysitting that breaks workflow and encourages distraction instead of close scrutiny. Speed improvements tie directly to testing, as rapid iteration allows earlier error detection and validation. This is how I prefer to use LLMs for search: faster models that give a quick response which I can then steer to the answers I am looking for, rather than trying to put in prompt/context engineering work ahead of time without knowing whether it would pay off. A much more intelligent model that could confidently one-shot any problem and resolve all edge cases would also resolve this concern, but I only see that possible in closed environments with many tests.

I expect my use will change, and I’m impressed by how much these tools have improved in the last six months. My message to foundational model companies is to focus on model speed and consistency over intelligence going forward. This is what I am looking for to more confidently use agents to speed up my development process. Failing early would also be a useful feature. I discovered the limitations of the models after running them for a certain amount of time, and it would be preferable if the model could gauge its own ability in some form, before users need to spend high amounts of inference to not solve the problem.

One problem I think will remain difficult long term is the ability for humans to express the details of their problem to the LLM. There is a lot that a person might have in their mind that is difficult to rapidly communicate with natural language, and defining it is often most of the work for a person to solve it themselves. This was a recurring difficulty in most of my projects, particularly the game development.